Cite report

IEA (2019), World Energy Investment 2019, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2019, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Report options

Fuel supply

Investment in upstream oil and gas

Upstream oil and gas investment is set for another modest rise in 2019

Shale remains dynamic, but the investment focus is shifting to conventional assets

In 2018, companies spent in aggregate slightly more than the guidance they provided to the market, encouraged by rising oil prices throughout the year (until the last quarter). We have revised upwards our 2018 estimates for the rise in global upstream spending in 2018, from 5% to 6%.

Our estimate for global upstream investment in 2019 is USD 505 billion, a 6% increase in nominal terms (a 4% increase in real terms) on the previous year. Three years of modestly higher spending still leave this figure nearly USD 300 billion lower than the peak reached in 2014.

Adjusted for declining upstream costs, the reduction in spending is less stark. The 35% reduction in nominal spending from 2014 to 2018 turns into a much smaller 12% fall in activity.

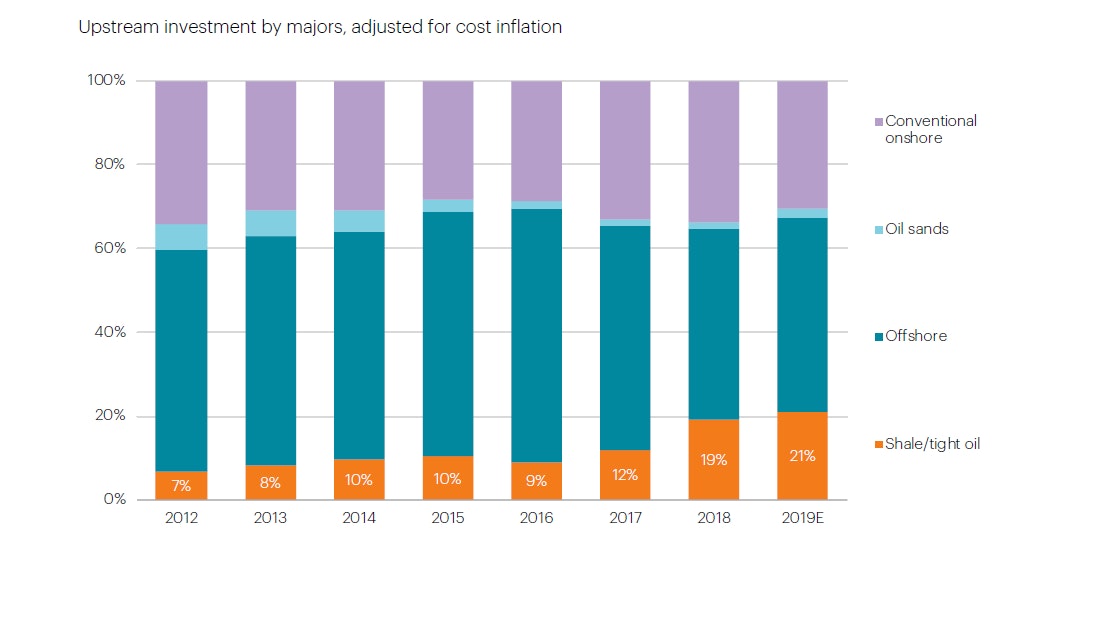

The main upstream story of the last few years has been a shift in spending towards shale (tight oil and shale gas) in the United States. The investment landscape for shale remains dynamic with the arrival at scale of the majors, but this is being offset by a more subdued outlook for most of the pure shale players, for whom the priority is now to live within their means.

The signs in 2019 are that the balance of spending is starting to shift again. In our assessment, the fastest growth in upstream investment this year is set to be in conventional projects, rather than in shale. This also means that some upstream markets that have been in the shadow of the United States in recent years are starting to move back into the limelight.

Shale has levelled off at around a quarter of total upstream spending

Conventional spending is turning the corner

The reaction of the large, conventional operators to lower prices since 2014 has had four main components:

- Maximise revenue from existing operations; the share of brownfield spending has risen, up to 67% of the total in 2018 from less than 60% in 2016.

- Cut costs wherever possible.

- A greater focus on smaller assets that can be brought to market more quickly, notably shale.

- Defer spending on more complex new projects until they are redesigned and simplified to be competitive at lower prices.

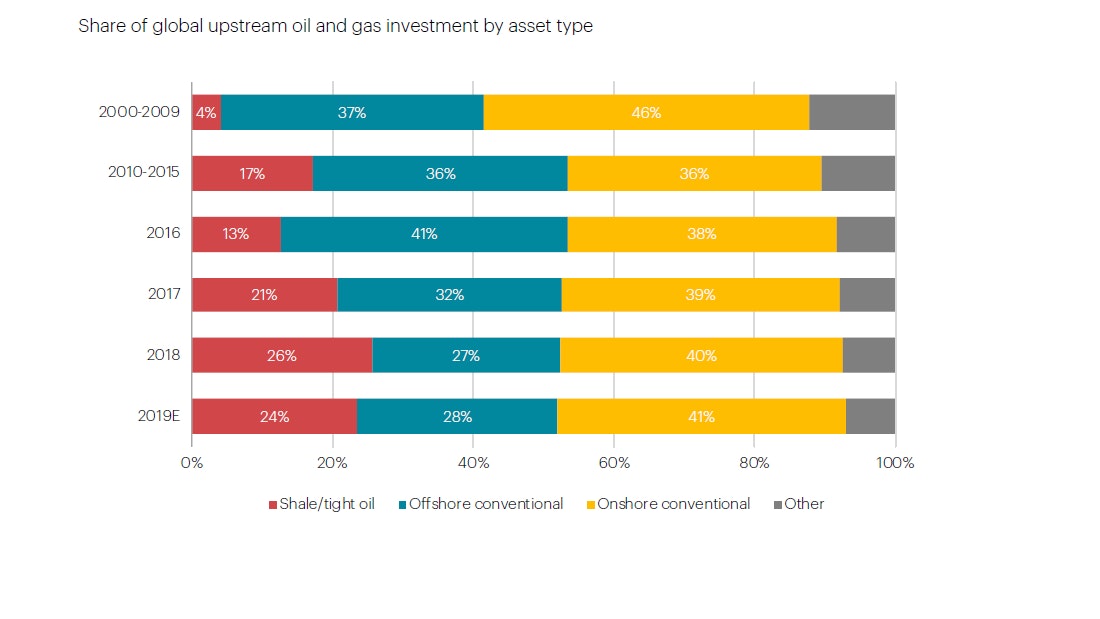

These changes were reflected in the composition of upstream spending. Conventional oil and gas projects remain the predominant channel for investment, but their two-thirds share of the total in 2018 was a historical low. Within this segment, spending on offshore projects has been squeezed hard; the offshore share in upstream spending fell by over 10 percentage points between 2016 and 2018.

There are signs in the 2019 guidance that conventional spending in general, and offshore investment in particular, may be turning a corner. This is being led by the Middle East and Latin America.

Shale assets have rapidly increased their weight in global upstream investment this decade, reaching 26% of the total in 2018. For 2019, we expect a marginal decline in this share, to 24%, as the reduction of investment anticipated by shale pure operators is only partially compensated by rising spending in shale basins announced by some of the majors.

Time for a rebound in conventional project approvals? (1/2)

Note: The NPS and SDS show the annual average of sanctioned resources between 2018 and 2025 under the IEA New Policy Scenario (NPS) and Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) respectively. Source: IEA analysis with historical sanctioned resources based on Rystad Energy (2019).

Time for a rebound in conventional project approvals? (2/2)

Note: NPS and SDS show the annual average of sanctioned resources between 2018 and 2025 under the IEA New Policy Scenario (NPS) and Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), respectively. Source: IEA analysis with historical sanctioned resources based on Rystad Energy (2019).

The offshore sector is showing clear signs of life

The last three years (2016-18) saw very low levels of conventional oil and gas resources being sanctioned for development. Approved conventional oil resources averaged 7 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe), 60% lower than the previous five years, while conventional gas resources, at 8.3 billion boe, were 40% lower.

If oil and gas demand continues to grow as in the NPS, then there would need to be a substantial increase in resources sanctioned for development to keep the market in balance. Guidance from companies suggests that such an acceleration in new project approvals is indeed possible in 2019.

Companies are only moving ahead with their highest- value projects, but several are expected to go ahead. Many of these are offshore: in the Gulf of Mexico, Guyana, the North Sea, and Brazil as well as large integrated liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects, such as the expansion of the Qatar terminals and the sanctioning of gas fields in the Rovuma basin off Mozambique.

The renewed attraction of offshore projects is linked to the precipitous decline in break-evens over the last few years due to lower costs for offshore supplies and services, shortened timing to bring first oil and gas into production as well as simplified and standardised project designs.

ExxonMobil expects its Guyana and Brazil’s Carcara deepwater projects to give an internal rate of return (IRR) in excess of 30%. Total anticipates its Angola offshore projects to achieve an IRR in excess of 20% at an oil price of USD 50/barrel.

After strong growth in 2017 and 2018, the rise in US upstream investment is expected to take a pause in 2019....

...and the Middle East and Latin America are seen leading the spending growth

Our estimates point towards rising spending in 2019 in almost all key producing regions. In the Middle East, some of largest national oil companies (NOCs), including Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, Qatar Petroleum, and Kuwait Petroleum Corporation, have signalled their intention to step up their upstream activity in order to sustain oil production levels and meet rising domestic gas needs.

Upstream spending in Latin America is expected to increase in 2019 by just above 10%, driven mainly by Brazil, Guyana, Argentina and Colombia. In its five-year strategy, Petrobras unveiled higher spending, and several international companies are increasing their activities in Brazil’s offshore.

Investment is expected to be on the rise again also in Europe, driven by higher spending in the North Sea, including the first phase of the massive Johan Sverdrup field. African upstream spending is also set to trend higher after a very subdued period in recent years.

With the exception of Rosneft, large Russian companies are set to keep upstream spending around or slightly below the levels in 2018 (in dollar terms). Investment activity will be shaped in practice by the OPEC+ agreement, as well as by anticipated changes to Russia’s upstream tax regime.

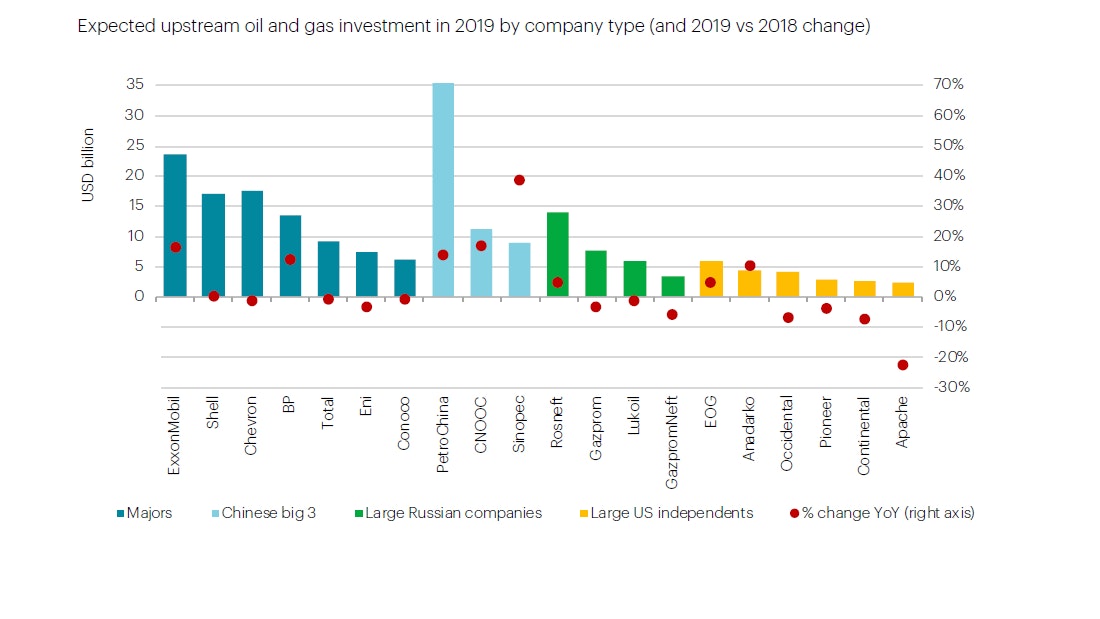

Overall investment by NOCs remained quite resilient during the downturn and their spending is expected to rise in 2019. Chinese NOCs have announced large increases in their capital budgets, and this will help keep the overall share of NOCs in total upstream investment at around 43% in 2019, close to historical highs.

Upstream investment in 2019 varies by company

Note: CNOOC = China National Offshore Oil Corporation Source: IEA analysis with calculations based on company reports and guidance

The share of NOCs in total investment remains close to record highs

Note: Data for 2019 are IEA estimates based on company guidance, consultations with industry experts, and other sources. Source: IEA analysis with data based on company reports and Rystad Energy (2019).

Diverging company trends in investment activity in the United States

The share of the United States in global upstream spending has risen from 17% to 24% over the last ten years, but this upward trend is likely to be checked in 2019.

There are divergent investment trends between the US independents and the majors. Increased demands for capital discipline and investor returns are putting a cap on spending by the independents, especially for those companies operating exclusively in shale plays. However, the impact on production is likely to be mitigated by a decrease in the inventory of drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) and further operational efficiency.

Pioneer, Continental, WPX Energy, Parsley Energy, Centennial Resource Developments, Apache, and Noble all announced spending cuts for 2019 (while maintaining robust production growth projections). Our assessment, based on guidance provided by pure-shale operators and US independents, suggests that upstream investment from this group in 2019 could be lower by some 6% than in 2018. For the moment, the commitment to capital discipline appears to be holding despite higher prices.

In contrast, international oil companies have maintained or increased their upstream US plans. Exxon and Chevron have made the Permian Basin a centrepiece of their strategies, while Shell and BP are increasing their positions. This will give the majors a much greater role in US supply and could encourage further consolidation in the sector.

As a result, 2019 is on track to be the first year where investment growth in shale assets passes from independents to big oil companies. This is a remarkable change for a sector which has until now been dominated by smaller operators. The growing footprint of large players means that investments might become less volatile.

The majors are making their mark on shale

Source: IEA analysis with calculations based on IEA upstream investment cost indices, company reports and Rystad Energy (2019).

The shift to shorter-cycle conventional projects continues...

...reflecting industry preferences to limit upfront capital outlays and reduce exposure to longer-term risks

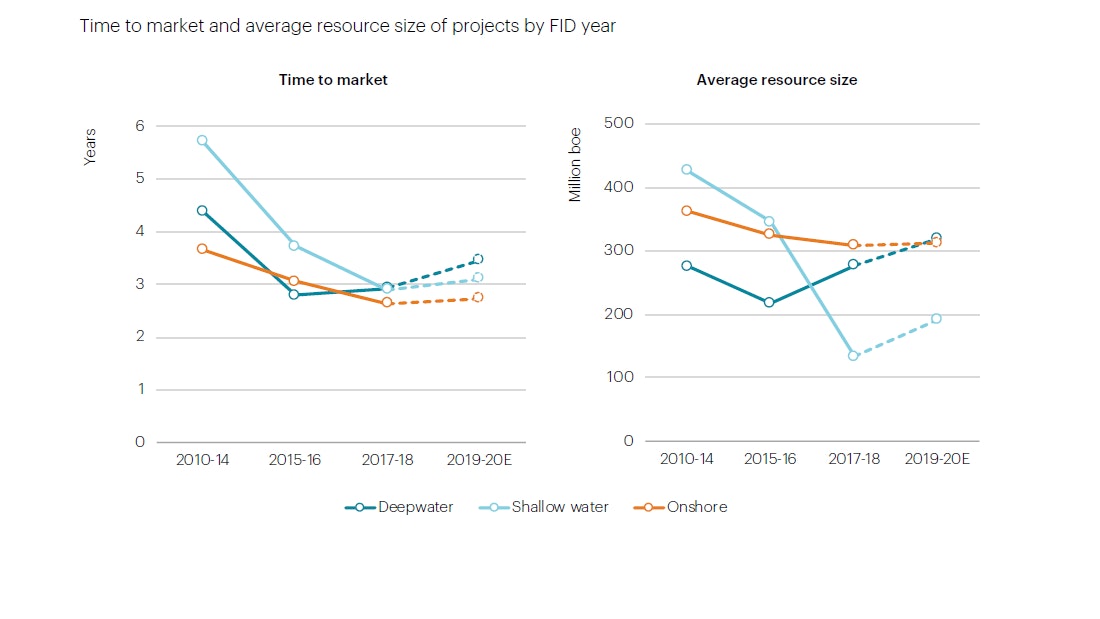

The emphasis on shorter cycle projects highlighted in previous editions of the World Energy Investment Report (see IEA, 2018a) continues in 2019. There remains a preference among many operators to limit upfront capital spending, accelerate paybacks, and reduce exposure to long-term risks. Greater exposure to shale is one aspect of this, but companies are also rethinking the way they approach conventional projects.

Since the 2014 downturn, the oil and gas industry has moved away from its traditional focus on larger-scale, capital-intensive projects with long lead times. The trend has instead been to fast-track the execution of smaller projects or to divide large projects into multiple phases. Lead times for new projects have fallen sharply.

In the offshore sector in particular, projects are moving from the final investment decision to first production much more quickly than they used to, and at lower costs. This experience is now encouraging operators to sanction new and larger projects. Based on guidance announced by companies, we expect that in 2019 and 2020 the average size of offshore projects will increase by over 20% but without a corresponding increase in time-to-market.

The overall result is a shift away from large, bespoke projects (often characterised by delays and cost overruns) towards smaller, standardised ones, with a strong accompanying focus on efficiency and capital discipline. This also means that the oil and gas industry is increasingly relying on assets that generate cash flow more quickly but also that deplete at a more rapid pace. This could increase the possibility of market volatility.

Discoveries are at record lows, but exploration may be turning a corner...

Source: IEA analysis with calculations based on Rystad Energy (2019).

...and investment in exploration could see a slight uptick in 2019

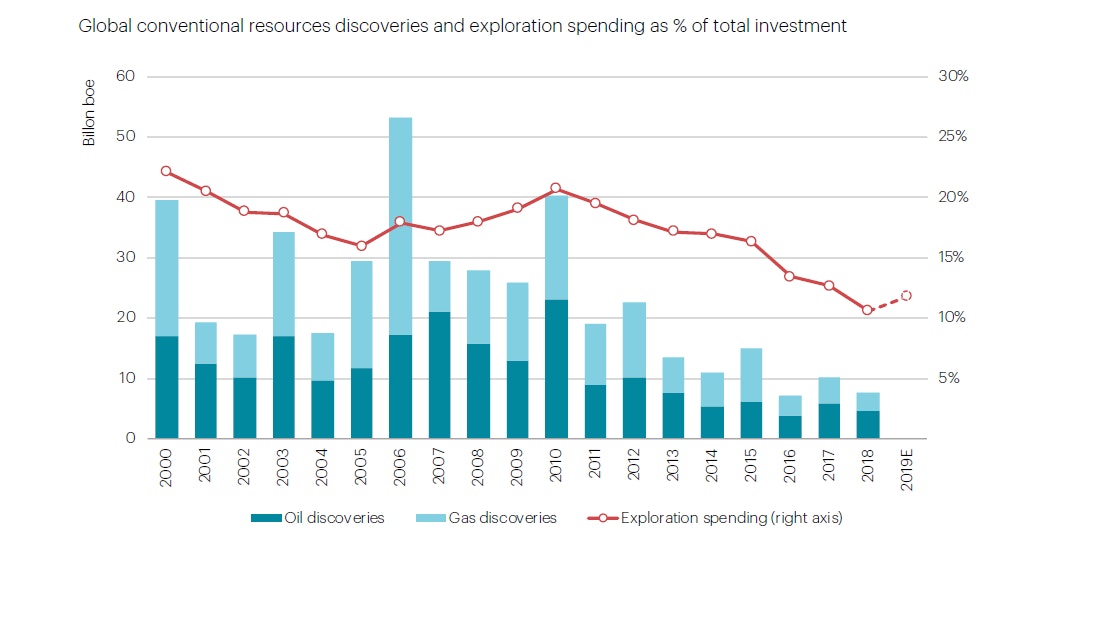

After many years of decline, investment in exploration is set to rise to USD 60 billion in 2019, an increase of 18%. Nonetheless, the share of exploration in total upstream investment remains almost half the level in 2010.

Companies started to reduce exploration investment even before the 2014 oil price collapse, but the downturn accelerated the trend, and spending in the sector almost halved between 2014 and 2018. While companies are expected to keep spending on exploration under close control also in 2019, the anticipated increase would be the first one since 2010.

Similar to other parts of the upstream industry, the exploration sector has undergone significant structural changes in recent years. Budget cuts and financial constraints have driven the deployment of more efficient rigs and a decline in the cost of seismic surveys, ultimately leading to an overall reduction in the average project break-even.

The contraction of exploration activities translated into a massive reduction in discovered resources. Between 2014 and 2018, the discoveries of conventional crude oil amounted on average to 5.2 billion boe per year, two- thirds lower than the average of the previous decade (and over one-fifth of the oil discoveries since 2015 were in one country, Guyana). The trend was similar also for gas discoveries, at 5.0 billion boe per year in the 2014-18 period versus 15.1 billion boe in the previous decade.

However, some signs of recovery have already been evident in Q1 2019, with important offshore discoveries in Guyana (again), South Africa, and Angola.

Upstream costs have edged higher, but with few signs of overheating...

...with overall costs still more than 20% below the peaks reached in 2014

Note: OCTG = oil country tubular goods; D&C = drilling and completion.

Doing more with less – oil and gas industry keeps costs in check

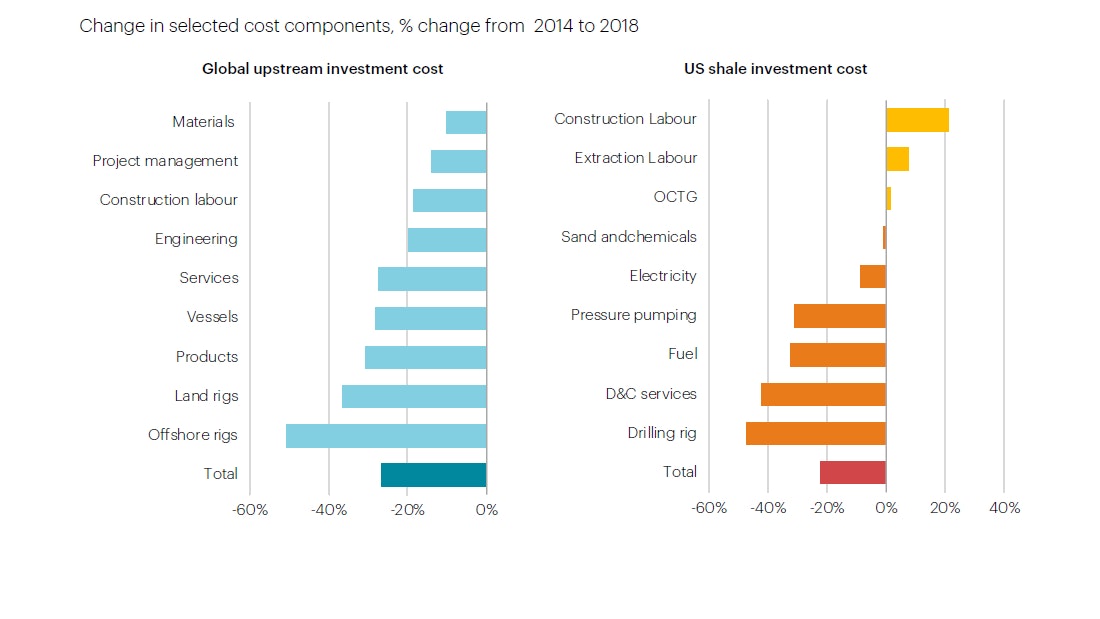

Following a 3% rise in 2018, global upstream costs are expected to rise by around 1% in 2019. This overall trend is the product of two diverging factors: on the one hand, increased upstream activities and the consolidation of the service industry are supporting higher costs; on the other hand, companies continue to target cost savings with limited pricing concessions to service companies, helped by the continued overhang in the market for some services and equipment.

The picture varies across regions and sectors. The steep fall in prices in the offshore industry has finally halted, although they remain at very depressed levels. For most equipment and services, cost inflation is still limited, while materials including cement and steel are declining on the back of weaker economic fundamentals.

Costs for the conventional upstream sector are still significantly below the levels seen in 2014. Rig rates, both onshore and offshore, are over 30% lower, but all key cost components are showing a significant discount compared with the pre-downturn levels.

Costs in the shale industry are affected by a different set of factors. We expect cost inflation in 2019 of around 5% – lower than the 12% seen in 2018.

The key inflationary components for shale activities in 2019 are shortages of personnel, which push costs higher in the drilling and completion (D&C) services component, and drilling rigs, where the market for high- spec rigs remains tight even though the level of activity is also slowing somewhat.

The costs of pressure pumping and proppants are expected to taper off as a large increase in sand supply from new local production sites is helping to keep pricing and transportation costs down in the Permian Basin.

Investment in oil and gas midstream and downstream

The logjam of new LNG project approvals has been broken...

...and 2019 could be a big year for new gas infrastructure

After a two-year lull, four new LNG projects have been sanctioned since mid-2018 (three in North America and an FLNG in offshore West Africa). These projects will add almost 60 billion cubic metres (bcm) of nominal liquefaction capacity by 2025, with overall investment of over USD 40 billion.

A bullish outlook for gas demand is encouraging companies to consider the sanctioning of additional LNG plants. The ones considered most likely to reach FID in 2019 include the 45 bcm capacity expansion announced by Qatar, the Arctic LNG 2 project in Russia, and the ExxonMobil-led consortium in Mozambique Area 4, among others. If all those projects reach FID this year, 2019 will represent a historical record for decisions on LNG capacity expansion.

Recent years have seen also a wave of new major pipeline projects. Gazprom led developments, with three major pipelines announced to be completed and operational by end of 2019: the 55 bcm/yr Nord Stream II to Germany through the Baltic Sea; the 38 bcm/yr Power of Siberia to China, and the Turkstream connecting Russia and Turkey through the Black Sea with two

15.75 bcm/yr lines.

In the United States, the shale revolution has triggered the development of several new pipelines. Texas and the prolific Permian Basin is the epicentre of the development of new pipelines, mainly aimed at connecting rising oil and gas production from the basin to the Gulf Coast.

The construction of new oil pipelines has been prioritised so far in the Permian, but the lack of evacuation capacity for associated gas production has raised concerns as a possible constraint for further oil supply growth. The debottlenecking of gas supply in the Permian is expected by end-2019 with the entering into operation of the 20-bcm/yr Gulf Coast Express pipeline.

Refining investment continues to rise, led by Asia and the Middle East...

Note: The figures reflect estimates of ongoing capital expenditures over time and do not include maintenance capex.

...in part to adapt to changing characteristics of demand and supply

Note: FCC = fluid catalytic cracker

Refiners are responding to the IMO 2020 regulation in diverse ways

Non-exhaustive examples of IMO-related refining investments

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Residue desulphurisation | Removes sulphur from vacuum residue and produces more LSFO | - SK Innovation: building a vacuum residue desulphurisation facility to be operational from 2020 |

| Upgrading | Adds residue cracking units to reduce HSFO production and increase lighter products production | - ExxonMobil: investing in refinery upgrades in the United Kingdom (Fawley) and Singapore (Jurong) - S-OIL: commissioned a residue upgrading complex in 2018 |

| Solvent de-asphalting (SDA) | Processes heavy fuels to clean middle distillates and provides increased crude flexibility | - Shell: commissioned a new SDA unit at its Pernis refinery in 2018 - Neste: started up an SDA at its Porvoo plant - Hyundai Oilbank: operating an SDA unit at its Daesan plant |

| Yield adjustments | Adjusts configuration in favour of gasoil relative to gasoline by redirecting some of the atmospheric gasoil and residue streams away from FCCs | - Mostly in the United States |

Notes: HSFO = high-sulphur fuel oil, LSFO = low-sulphur fuel oil, FCC = fluid catalytic cracker. The IMO regulation limits the sulphur content in marine fuels to no more than 0.5% from 2020.

Refiners are gearing up for changing market environments

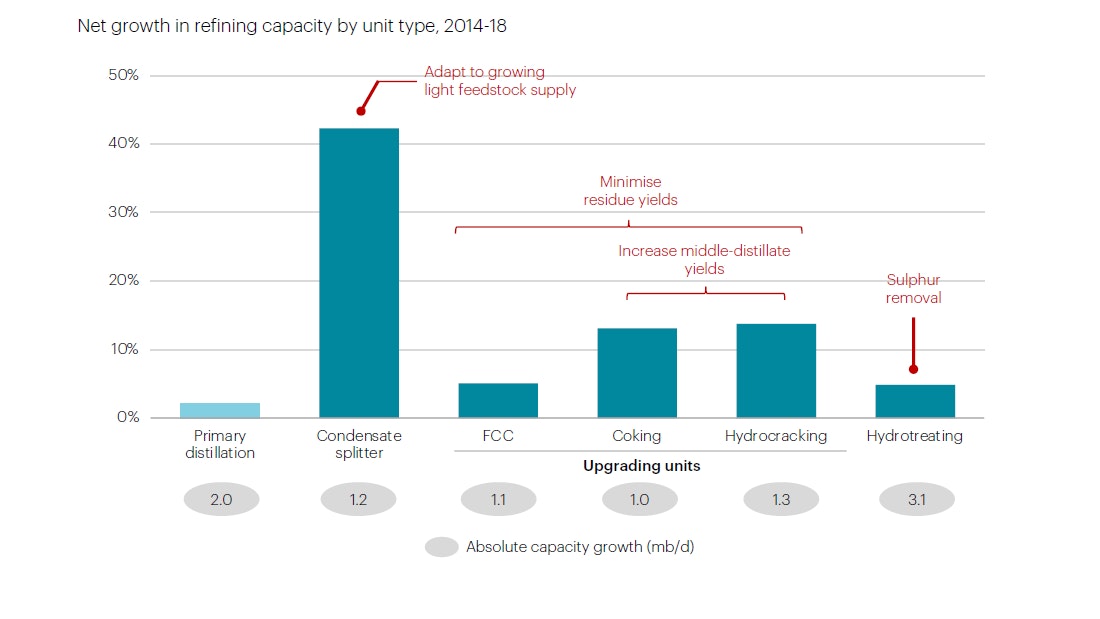

After rising from a dip in 2015, refining investments have remained high, reflecting a wave of investment decisions in recent years. Capital spending on refining units (new units and upgrades) and maintenance amounted to USD 43 billion and USD 24 billion, respectively. This is expected to result in large amounts of new capacity coming online in 2019 and beyond, suggesting potentially greater competition in the refining sector in the years ahead.

Around 70% of the investment in refining units in 2018 was made in Asia (where regional product demand is growing) and the Middle East (where companies are pursuing vertical integration).

Several companies in the Middle East, such as Saudi Aramco, are also pursuing investment opportunities in growing Asian markets, such as China, India, Korea, and Malaysia.

In addition to primary distillation capacity, refiners are increasingly investing in various upgrading and desulphurisation units to adapt to changing demand, supply, and regulatory environments:

- Upgrading capacities grew by 9% between 2014 and 2018 to minimise the production of heavy residue. Investments in coking and hydrocracking units were higher, reflecting refiners’ efforts to target more middle distillates production (such as diesel).

- Tightening product quality standards, such as the Euro emissions standards and the International Maritime Organization’s sulphur cap, underpinned growing investments in desulphurisation units, which are set to grow rapidly in the coming years.

- Condensate splitter capacities registered a strong 42% growth, primarily in the United States, Iran, and Korea in light of a growing light feedstock supply.

Coal supply investment

Coal supply investment increased for the first time since 2012...

...but the divestment movement is gathering momentum

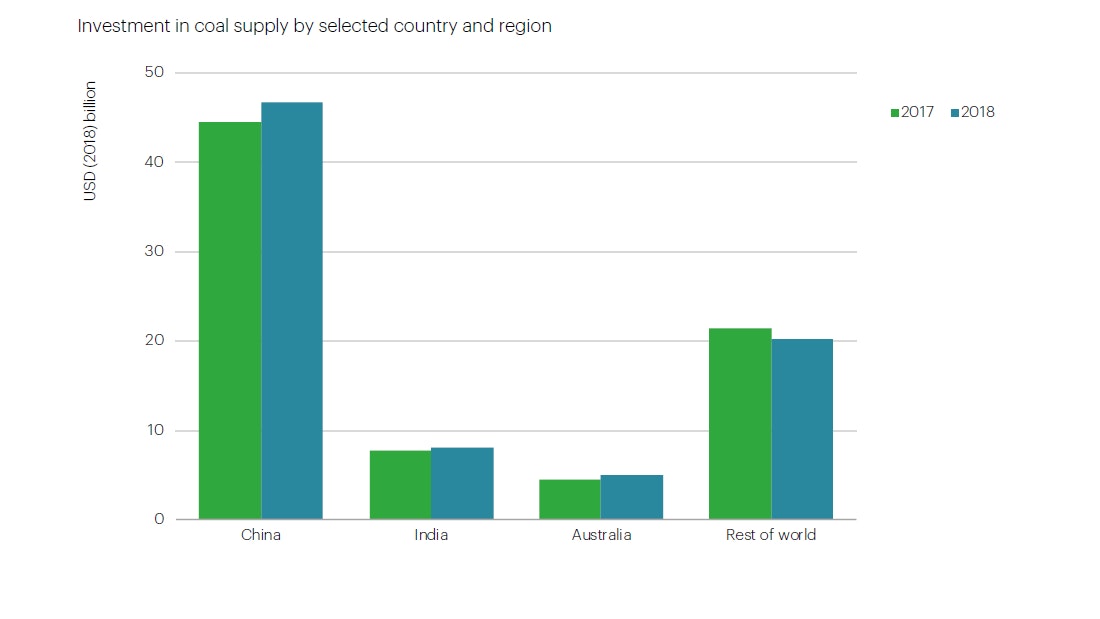

In 2018, global investment in coal supply increased by 2% to USD 80 billion as investment ramped up in almost all the major producing regions (China, India, and Australia). This was the first increase since 2012, although investment remains far below the peaks reached in the early 2010s. The investment was almost all for sustaining production levels rather than opening new mines.

China, accounting for 45% of global coal production, remains the key driver of total investment in the sector. China’s investment in coal supply increased to over USD 45 billion in 2018 after five consecutive years of decline. Most investments were aimed at sustaining production and increasing productivity and safety by closing unsafe, inefficient mines and replacing them with more efficient ones.

Coal supply investment in India grew by 5% in 2018, underpinned by policy favouring domestic production while reducing imports as much as possible, amid a substantial growth of coal consumption driven by economic growth and higher power demand.

Rising coal prices and soaring seaborne coal trade over the last couple of years are providing signals to coal- exporting companies to increase capital spending, but there are few signs of a strong pick-up in spending. The stronger capital discipline put in place during the 2013-15 price downturn has relaxed, but expansionary capital expenditures are scarce, in particular for greenfield projects.

The divestment movement – where investors allocate capital away from the coal sector – is gaining steam. China’s State Development & Investment Corporation, some Japanese trading companies, and QBE, the largest Australian insurer, announced the end of exposure to the sector. Glencore, the world’s largest coal exporter, declared a coal production cap, in response to investor pressure.

Biofuels investment

Biofuels investment has risen somewhat from recent low levels...

Note: Biofuels include crop based ethanol, cellulosic ethanol, fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) biodiesel, hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), among others. Source: IEA analysis with estimates based on data from IEA (2018c) and F.O. Licht (2019).

...but the sector needs further policy support to achieve the SDS trajectory.

In 2018, investments in transport biofuels production capacity increased by 12%, led by China where 10% ethanol blending is to be rolled out nationwide, and the United States where most investment went towards adding production capacity at existing plants. Brazil saw stable capacity additions, with record ethanol demand in 2018 and the RenovaBio biofuel policy due to commence in 2020.

The increase was partly offset by a decline in investment in Europe, largely due to a weakening long-term outlook for policy support for conventional biofuels in the updated Renewable Energy Directive, and in Southeast Asia where countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia have production overcapacity.

Investment in ethanol production capacity accounted for 80% of the biofuels investment over the last five years, one-tenth of which went to advanced ethanol (cellulosic ethanol). The remaining 20% was in biodiesel and the growing trend of investment in hydrotreated vegetable oil production.

Biofuels investment represented less than 1% of the total investment in fuel supply. In absolute terms, the investment in 2018 was 70% below its level from a decade ago when investment was boosted by policy support and rapid market expansion in Europe and the United States.

A stagnation in investment over the past several years was led by the “blend wall” effect in the United States, which refers to structural challenges relating to vehicle suitability and fuel distribution infrastructure for higher ethanol blends, challenging economic conditions in the Brazilian market and policy uncertainty in Europe, combined with lower oil prices from late 2014.

Investment in the sector would need to increase six fold in the next decade to achieve the trajectory in the SDS, indicating the importance of increased policy support to scale up sustainable biofuel deployment and facilitate innovation for advanced biofuels.