IEA (2024), Reducing the Cost of Capital, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/reducing-the-cost-of-capital, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Executive summary

Clean energy investment in most emerging and developing economies has yet to take off: A high cost of capital is a major reason why

How emerging market and developing economies (EMDE1) meet their rising energy needs is a pivotal question both for their citizens and for the world. Cost-competitive clean energy technologies open the possibility to chart a new, lower-emissions pathway to growth and prosperity, but capital flows to clean energy projects in many EMDE remain worryingly low. Global clean energy investment has risen by 40% since 2020, reaching USD 1.8 trillion in 2023, but almost all the recent growth has been in advanced economies and in China. EMDE account for around 15% of the total, despite accounting for about a third of global gross domestic product and two-thirds of the world’s population. India and Brazil are by a distance the largest EMDE clean energy markets.

All pathways to successful global energy transitions depend on expanding capital flows to clean energy in fast-growing EMDE. With growing international attention to this issue, the International Energy Agency (IEA) was tasked by the Paris Summit on a New Global Financing Pact in June 2023 to make recommendations on how to bring down the cost of capital for clean energy investment in EMDE. This report answers that request, building on previous IEA analysis and on new survey data collected for the IEA’s Cost of Capital Observatory project.

Our survey of leading financiers and investors confirms that the cost of capital for utility scale solar photovoltaic (PV) projects in EMDE is well over twice as high as it is in advanced economies. This reflects higher real and perceived risks in EMDE at the country, sectoral and project levels. An elevated cost of capital pushes up financing costs and makes it much more difficult to generate attractive risk-adjusted returns, especially for relatively capital-intensive clean technologies. As a result, EMDE can end up paying more for clean energy projects or they can miss out altogether. Solar PV plants and other clean energy projects tend to involve a relatively higher share of upfront expenditure and a lower share of operating expenses in total project costs. If countries cannot afford high upfront costs, they can be locked into polluting technologies that might initially be less expensive but require persistent spending on – and combustion of – fossil fuels for their operation.

Cost of capital for utility-scale solar PV and storage projects taking final investment decision in 2022

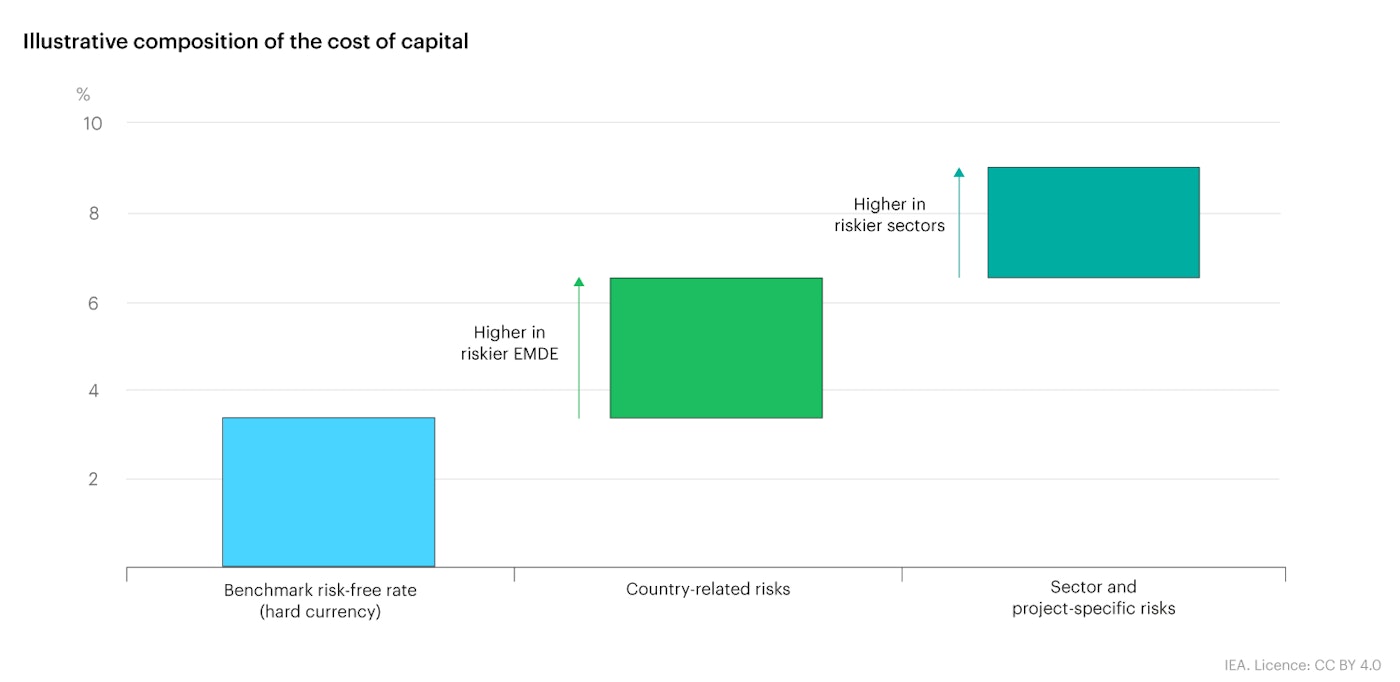

OpenCountry and macro factors are a major contributor to the high cost of capital for clean energy projects, but so too are risks specific to the energy sector

Broad country-related risks and macroeconomic factors typically explain a large share of country-by-country variations in the cost of capital. These include the rule of law and sanctity of contracts, as well as concerns about currency fluctuations and convertibility. As the balance of capital spending on energy in EMDE shifts away from dollarised, globally traded commodities, such as oil, towards clean energy projects that rely on domestically generated revenues, the overall quality and predictability of the domestic business environment become even more important for investors. Mechanisms that mitigate these risks include guarantees against expropriation and facilities to reduce the cost of currency hedging. However, over the longer term there is no substitute for efforts to tackle the underlying issues by strengthening national institutions, reducing inflation, and deepening local capital markets and financial systems. EMDE that have successfully scaled up clean energy investment, including India, Brazil and South Africa, have all relied heavily on domestic sources of capital.

There are also project- and sector-specific risks that can be addressed directly by energy policy makers and regulators; these are the focus of this report. In the case of clean energy generation projects in the power sector, key issues highlighted by survey respondents relate to sector regulations, the reliability of revenues – dependent mainly on the off-taker’s ability to pay on time – and the availability of transmission infrastructure or land, and how all these issues are defined in contracts. Such project- and sector-specific elements can account for 20-30% of the higher cost of capital in EMDE. This report provides detailed insights into these factors, how they vary across parts of the energy sector, and what can be done to address them. There are plenty of positive examples in EMDE where clear regulation, a vision and intent to move ahead with clean energy transitions, and a readiness to work with the private sector have yielded impressive results.

The required increase in EMDE clean energy investment is huge, but almost all of it involves mature technologies supported by tried and tested policies

From USD 270 billion today, annual capital investment in clean energy in EMDE needs to rise to USD 870 billion by the early 2030s to get on track to meet national climate and energy pledges, and to USD 1.6 trillion in a 1.5-degree pathway. The increases are needed across a range of technologies and sectors, but three areas stand out: almost a quarter of the total clean energy investment over the next ten years goes to utility-scale solar and wind projects, and another quarter is made up of investment in electricity networks and in efficiency improvements in buildings together. A small fraction of the total investment spend – less than USD 50 billion per year – would be sufficient to ensure universal access to electricity and to clean cooking fuels.

The increase in spending is steep but almost all the required EMDE investment is in mature technologies and in sectors where there are tried and tested policy formulas for success. This would give EMDE a firm foothold in the new clean energy economy, with major benefits for energy access and security, sustainable growth, and employment, as well as for emissions and air quality. Only about 5% of the cumulative EMDE clean energy investment needs to 2035 are in sectors that depend on nascent technologies such as low-emissions hydrogen, hydrogen-based fuels, or carbon capture, utilisation and storage.

Investment in emerging market and developing economies by sector’s commercial and technological readiness, cumulative 2024-2035

OpenKey roles for enhanced international support and concessional finance

Investment on this scale will mean scaling up all sources of finance, with a vitally important role for well-coordinated, enhanced international financial and technical support. As part of the global push to expand and improve finance for sustainable development, we estimate that a tripling of concessional funding for EMDE energy transitions will be required to get EMDE on track for their energy and climate goals. Not all projects or countries require this kind of support, and it cannot replace needed policy actions or institutional reforms. But, used strategically, it can help countries remove barriers that are slowing clean energy investment – including weaknesses in project preparation, data quality, and energy sector policies and regulation that push up the cost of capital – and bring in much larger volumes of private capital. Targeted concessional support is particularly important for the least developed countries that will otherwise struggle to mobilise capital. Stronger coordination among governments, development finance institutions, private financiers and philanthropies will be essential to help EMDE navigate and understand the different financing instruments, risk-mitigation and credit enhancement tools that can help projects get off the ground.

Lowering the cost of capital by 1 percentage point could reduce financing costs for EMDE net zero transitions by USD 150 billion per year

Our analysis shows that capital costs – e.g. for land, buildings, equipment – are usually the largest single element in total clean energy project costs in advanced economies, whereas in EMDE the largest element is financing costs. Financing costs for utility-scale solar PV projects in EMDE, for example, can constitute around half or more of the levelised cost of electricity. Efforts to decrease the cost of capital in EMDE are not only crucial for investors but also for the overall affordability of energy transitions for consumers. We estimate that narrowing the gap in the cost of capital between EMDE and advanced economies by 1 percentage point (100 basis points) could reduce average clean energy financing costs in EMDE by USD 150 billion every year.

Recommendations on how to bring down the cost of capital for clean energy investment in EMDE

Multiple factors affect the cost of capital and many of the economy-wide risks lie outside the remit of energy decision makers, but the quality of energy institutions, policies and regulations still matters greatly. In this report, we highlight the importance of a clear vision and implementation plan for energy transitions, backed by reliable data and support with project preparation. We underscore the need for enhanced international support and collaboration. Using case studies and EMDE country examples, we also explore in detail some specific risks and applied solutions. Findings are presented here under four headings that reflect recurring themes from our discussions with investors and policy makers: the importance of good policy and regulation, reliable payments, timely permitting and availability of infrastructure, and tailored support for new and emerging technologies.

- Policy and regulatory requirements for clean energy projects vary widely across different parts of the energy economy, although a common denominator is the need for regulations to be technically sound, clear and predictable. Regulatory uncertainties in the power sector are a major concern, especially in new areas such as energy storage or privately financed grids. Strong regulatory frameworks for efficiency, including building codes and stringent minimum energy performance standards for appliances as seen in Chile, are a necessary condition to scale up investment in these sectors. South Africa’s experience with well-designed, regular procurement programmes for renewables has been very effective to jump-start battery storage investment and deployment.

- Payment and revenue risks can be offset by wider availability and use of guarantees, alongside efforts to strengthen the underlying financial health of the entities involved. Delays in payment of power purchased by off-takers, generally state-owned utilities, have been a regular concern for investors and financiers of renewable generation projects in EMDE (except for more mature markets that have already seen considerable deployment of solar PV and wind). Greater availability of guarantees that cover such payment delays, which are being introduced in various African countries for example, can help to reduce risks and unlock more investment in countries that are seeking to scale up renewable power. This implies increasing the capital allocated for guarantees by international financial institutions.

- Timely permitting and co-ordinated build-out of grids increases the predictability of project timelines and avoids connection delays, a risk that worries investors more and more, including in EMDE with a good track record of clean power projects. In the case of hydropower for example, identifying viable sites and conducting environmental due diligence can cause significant construction delays. Similar issues are highlighted by investors for grids and utility-scale solar and wind, especially in countries with high shares of variable generation. India’s experience with solar parks where tenders were put in place with land provided have reduced risks and enabled lower financing costs. Tenders to allocate transmission around green corridors are also on the rise. As the share of renewables increases, it is easier to earmark transmission lines as “green”, given these are needed almost exclusively to evacuate existing or expected solar and wind. Their green characteristics can also help attract high levels of private international capital. Bringing in the private sector to build transmission lines through project finance structures (with contracts like those successfully applied in generation), as seen in Brazil and various other Latin American countries, has a proven track record and could be more widely applied.

- Some new and emerging technologies and sectors require tailored support to address specific risks, such as the lack of charging infrastructure for electric vehicles or technological risk associated with first-of-a-kind advanced biofuel projects. These sectors will need tailored solutions such as targeted tax credits or first loss guarantees, alongside complementary measures such as consumer access to low-cost auto loans for electric vehicles and pricing reforms that make electricity competitive with (often subsidised) transport fuels. As with other growth markets, governments should consider renewable fuel standards or biofuel mandates such as those applied in Indonesia to provide stable market conditions for investors.

References

References to EMDE in this report exclude China.

References to EMDE in this report exclude China.